Golden Rice

Rob Bertram

Chief Scientist for Food Safety, USAID

About the Lecture

More than two billion people worldwide suffer from micronutrient malnutrition due to deficiencies in minerals and vitamins. Poor people in developing countries are most affected, as their diets are typically dominated by starchy staple foods, which are inexpensive sources of calories but contain low amounts of micronutrients. The highest numbers of people affected by mineral and vitamin deficiencies live in Africa and Asia. For instance, vitamin A and zinc deficiency are leading risk factors for child mortality. Iron and folate deficiencies contribute to anemia, physical, and cognitive development problems. The problem is compounded by the effects of climate change, with rising carbon dioxide levels reducing the availability of zinc, iron, protein and key vitamins in wheat, rice and several other staple crops. By 2050, hundreds of millions more people could slip below the minimum thresholds of these nutrients needed for good health.

This lecture will explore the opportunities for applying genetic engineering to simultaneously improve nutrient content and resilience to environmental stressors, such as heat, drought, and salinity. The pioneering development of Golden Rice will be used to illustrate both the challenges and the potential of biofortification to address vitamin A deficiency, which remains a serious public health concern in high rice consuming countries of South and Southeast Asia.

Suggested Readings:

(1) Swamy BPM, Samia M, Boncodin R, Marundan S, Rebong DB, Ordonio RL, Miranda RT, Rebong ATO, Alibuyog AY, Adeva CC, Reinke R, MacKenzie DJ. Compositional Analysis of Genetically Engineered GR2E “Golden Rice” in Comparison to That of Conventional Rice. J Agric Food Chem. 2019 Jul 17;67(28):7986-7994. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b01524. Epub 2019 Jul 8. PMID: 31282158; PMCID: PMC6646955.

(2) Van Der Straeten D, Bhullar NK, De Steur H, Gruissem W, MacKenzie D, Pfeiffer W, Qaim M, Slamet-Loedin I, Strobbe S, Tohme J, Trijatmiko KR, Vanderschuren H, Van Montagu M, Zhang C, Bouis H. Multiplying the efficiency and impact of biofortification through metabolic engineering. Nat Commun. 2020 Oct 15;11(1):5203. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19020-4. PMID: 33060603; PMCID: PMC7567076.

(3) Iqbal MS, Palmer AC, Waid J, Rahman SMM, Bulbul MMI, Ahmed T. Nutritional Status Among School-Age Children of Bangladeshi Tea Garden Workers. Food Nutr Bull. 2020 Oct 21:379572120965299. doi: 10.1177/0379572120965299. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33084406.

(4) Oliva N, Florida Cueto-Reaño M, Trijatmiko KR, Samia M, Welsch R, Schaub P, Beyer P, Mackenzie D, Boncodin R, Reinke R, Slamet-Loedin I, Mallikarjuna Swamy BP. Molecular characterization and safety assessment of biofortified provitamin A rice. Sci Rep. 2020 Jan 28;10(1):1376. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57669-5. PMID: 31992721; PMCID: PMC6987151.

About the Speaker

Rob Bertram is the Chief Scientist in USAID’s Bureau for Resilience and Food Security, where he serves a senior advisor on agriculture and nutrition in the implementation of Global Food Security Act. In this role, he leads USAID’s evidence-based efforts to advance research, technology and implementation in support of the U.S. Government’s global hunger and food security initiative, Feed the Future. He coordinates the Bureau for Food Security’s research portfolio spanning the U.S. University Feed the Future Innovation Labs, the CGIAR and other International Agricultural Research Centers, public-private partnerships in biotechnology, all of which collaborate and build capacity with partner country organizations. Previously, Rob served as Director of the Office of Agricultural Research and Policy in the Bureau for Food Security, and prior to that, guided USAID investments in agriculture and natural resources research. Before coming to USAID, he served with USDA’s international programs as well as overseas with the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) system.

Rob studied international affairs at Georgetown University and was a visiting scientist at Washington University in St. Louis.

He earned degrees in plant breeding and genetics at the University of California – Davis, the University of Minnesota and the University of Maryland.

Minutes

On November 20, 2020, by Zoom videoconference broadcast on the PSW Science YouTube channel, President Larry Millstein called the 2,429th meeting of the Society to order at 8:03 p.m. EST. He announced the order of business and welcomed new members. The Recording Secretary then read the minutes of the previous meeting.

President Millstein then introduced the speaker for the evening, Rob Bertram, Chief Scientist in the Bureau for Resilience and Food Security at the U.S. Agency for International Development. His lecture was titled, “Golden Rice: An Adventure in Science to Improve Nutrition.”

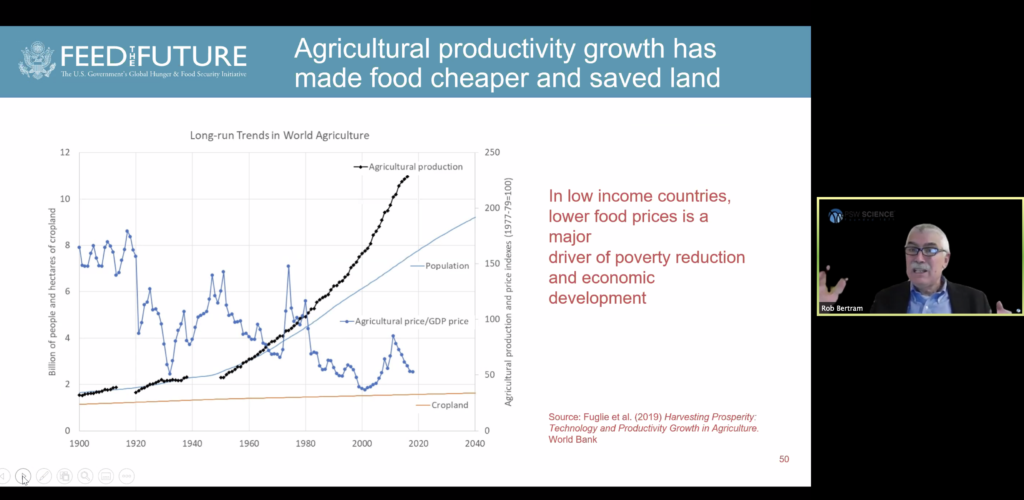

Nutrition is a unique global challenge. In 2007 and 2008, global prices of staple grains “skyrocketed,” adversely impacting the food security of people around the world. In response, the United States and other G7 member countries launched the Feed the Future initiative.

Stunted child growth is the standard marker for chronic malnutrition; it reaches 40-50% in some agricultural zones. Feed the Future’s objectives include reducing child stunting within those zones by 20%.

While the Feed the Future’s objective is global, diverse nutritional status demands diverse solutions. For example, energy deficits and micro-nutrient deficiencies remain high in low income countries because people do not eat enough animal-based foods, fruits, and vegetables. But, in high income countries, hunger and child stunting are comparatively low, and obesity is the principal nutritional challenge.

Bertram said diet is the best means for addressing nutritional deficiencies. He acknowledged movements away from animal-sourced foods in high income countries and advocacy for certain diets such as EAT-Lancet that purport to strike the ideal balance between climate impact and human health. But, he said, those diets are “cold comfort” for populations who cannot afford them.

Biofortification is an approach to mitigating micronutrient deficiencies by building nutrition into crops that, after an up-front investment, is affordable and sustainable.

Golden Rice is an example of biofortification. Populations with rice-centric diets experience higher rates of certain micronutrient deficiencies.

Rice is an available, affordable, and satiating food. But it is deficient in micronutrients, including Vitamin A, iron, and zinc. Vitamin A deficiency causes blindness, increases the mortality rate of children, and increases the fatality rate for certain diseases. In the Philippines, Vitamin A deficiency remains high in its rural and poor populations. In Bangladesh, the deficiency exists population-wide.

Bertram said rice lacks the genetic variability to breed a strain that would provide Vitamin A. To solve the nutrient deficiency, a partnership including Filipino and Bangladeshi scientists employed a biotechnological approach to produce Golden Rice. This rice, which is gold in color, bridges the gap in the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway by introducing two new genes, a phytoene synthase (from maize) and a carotenoid desaturase (CRTI) from a common bacterium. These genes lead to the equal production of beta-carotene and lycopene in the rice. Bertram said 100-g portion (uncooked) of Golden Rice could supply 30-40% of the recommended daily intake (RDI) of Vitamin A for children.

The chemical difference between golden and non-golden rice is “exactly the same,” except for the beta-carotene content. Because yield performance is also comparable, Bertram doubts Golden Rice will demand a premium price.

The Philippines and Bangladesh are currently reviewing Golden Rice for commercial propagation. Food regulators in Australia, Canada, the Philippines, the United States, and New Zealand have already approved Golden Rice for consumption.

Bertram said biofortified foods are more likely to gain popular acceptance than other means of addressing micronutrient deficiencies. Excepting Golden Rice, biofortified foods usually look the same and taste as good or better than the products they are intended to replace. Biofortified foods are also generally available to all members of a household, and they are sustainable and affordable after up-front investment.

Because nutrition impacts long-term health and productivity, Bertram said it should be seen as an economic issue in addition to a health issue. By considering economic impact, Bertram said the value in developing biofortified foods is indisputable.

Scientists are currently making progress in biofortifying crops through breeding such as pearl millet and beans to produce iron; wheat, rice, and maize to produce zinc; and sweet potatoes, cassava, and maize to produce Vitamin A. Biofortified crops are steadily increasing in acceptance from 1.7 million smallholder farm households growing them in 2014, to 8.5 million in 2019, reaching almost 50 million people.

Rice remains a challenge because it cannot be bred to increase iron and

Vitamin A content. Bertram said that objective may only be achieved through genetic engineering. He then responded to arguments against genetically engineered crops, including with examples of demonstrated pest-resistant food-safe crops and Green Revolution wheat seeds that have been widely grown for almost 50 years.

The speaker then answered questions from the online viewing audience. After the question and answer period, President Millstein thanked the speaker, made the usual housekeeping announcements, and invited guests to join the Society. At 10:06 p.m., President Millstein adjourned the meeting.

Temperature in Washington, D.C.: 11° C

Weather: Clear

Concurrent Viewers of the Zoom and YouTube live stream, 54 and views on the PSW Science YouTube and Vimeo channels: 177.

Respectfully submitted,

James Heelan, Recording Secretary